Biography

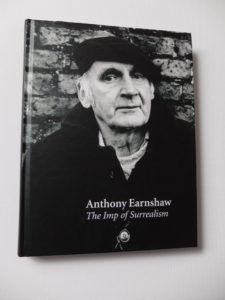

Photo by Michael Woods

Photo by Michael Woods

Anthony Earnshaw 1924-2001

Earnshaw was born in Ilkley, West Yorkshire. He attended Harehills School and left at the age of 14.

After school, he worked as an engineering fitter. Later, he was a lathe turner and indoor crane driver, while educating himself at Leeds City Library.

Aged 20, he became interested in surrealism, and with his lifelong friend, Eric Thacker devised surreal activities such as boarding and alighting from buses and trains at random.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, he met several like-minded people, including: Patrick Hughes, Ian Breakwell, John Lyle and George Melly.

Patrick Hughes persuaded Earnshaw to hold a retrospective at the Leeds Institute Gallery in 1966, which was followed by invitation by John Lyle, to show work in an exhibition in Exeter, “The Enchanting Domain”.

He met Gail Earnshaw in 1968 with whom he collaborated and showed work in a series of ‘Another G n T’ exhibitions. They married in 1985.

After leaving factory work in 1967, he began part-time teaching at Harrogate School of Art, then Bradford College of Art.

In 1972 he took up a fellowship at Leeds Polytechnic, Fine Art Department.

He left teaching in 1985 to concentrate on making art, writing aphorisms and making boxed assemblage.

In 1968 he collaborated with Eric Thacker on an illustrated novel, Musrum, published by Jonathan Cape, London, which became a cult classic. It was followed by a sequel, Wintersol, 1971, and Seven Secret Alphabets,1972.

Other publications include a cartoon, in the Times Educational Supplement, a wheeled bird named Wokker.

His work is in many private and public collections.

The Tate purchased an early work in 2012.

Flowers Gallery, London, represent Anthony Earnshaw.

TV and Radio Programmes

1987

View from Back‘O' Town, BBC Look North.

Two English Surrealists, dirercted by Alex Marengo, BBC2, 10 October.

View from Back‘O' Town, Radio Leeds interview.

1989

On the Edge, Tyne Tees Television, 7 December.

1993

Kaleidoscope, Radio 4, 11 January.

2003

A film, Flick Knives & Forks, directed by John Clayton.

Bibliography

1961

W.T.O. Oliver, Factory Hand's enigmatic watercolours, 31 Nov.

1968

George Melly, Musrum, Observer Colour Supplement, 6 October.

Philip Norman, Profile : Ahead of the Wolves, Sunday times, 31 March.

Jonothan Miller, Madly Lucid, Observer, 10 November.

Robert Nye, Fable or Joke, Birmingham Post, 23 November.

Anon., Odd looks for minister who writes ‘as I feel', Morning Telegraph, 27 December.

Pat Williams, Weird Word, Sunday Telegraph, 27 October.

Ivor Cutler, Dressing-table book, Sunday Times, 27 October.

Anon., Bumper fungus Book, Times Literary Supplement, 24 October.

Ray Gosling, I gave my copy to the trombonist, The Times, 26 October.

Martin Dodsworth, Duldrum, The Listener, 24 October.

David Piper, The poet dies again, Guardian, 8 November.

Anthony Powell, Surrealists at large, Daily Telegraph, 19 December.

Edward Lucie-Smith, Christmas Books 1, NewStatesman, 29 November.

Anon., Private Joke Book, Guardian 28 October.

Anon., "Indescribable' is the word, Halifax Courier, 25 October.

Alan R, Radnor, Visit a fantasy world, Evening Express, 2 November.

Anon., Musrum Developers.

Neil Spencer, Musrum.

1969

Douglas Wollen, Bookshelf, Methodist Magazine, March.

1970

George Melly, Revolt into Style, Alan Lane, The Penguin Press, Harmondsworth.

1971

Michael McNay, A misanthropic Christmas, Guardian 25 November.

1972

W. L. Webb, Books of the Day, Guardian, 30 November.

Peter Fuller, Anthony Earnshaw, Arts review, 18 November.

George Melly, Signs and portents, Guardian 30 November.

Anon., Too trendy for words, Daily Mirror 6 November.

Anon., Tony's seven ways of saying ABC, Yorkshire Evening Post, 29 December.

1973

Anon., The Star, 1 March.

Peter Mackarell, Surreal Humour, Times Educational Supplement, 23 February.

I.B., Secret's of an artist's Visual Humour, Express and Echo, Exeter, 9 January.

1979 George Melly, A cold wind brushing the temple (catalogue). Arts Council of Great Britain.

1980

John Lyle, The assassination of Pierot, Greenwich Theatre Gallery (catalogue), London.

Jeff Nuttall, Three Artists, Guardian.

Tony Pusey, Melmoth 2, London.

1982

‘Rover,' Leeds Other Paper, 26 March.

W.T,O. Oliver, Yorkshire Post.

John Hewitt, Boats of Splendour.

Rosanna Negrotti, Anthony Earnshaw, What's On.

1983

Patrick Hughes, More on Oxynoron, Penguin Books, New York.

1985

Miranda Strickland-constable, The Irrisitable Object, (catalogue) Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds.

1986

Ian Walker, The Spirit of Surrealism, Contrariwise ( catalogue) Glynn Vivian

Gallery, Swansea.

David Briars, Contrariwise, Art Monthly.

1987

Terry Waldron, Teeside vision mingled with a mean old world, Middlesbrough,

Evening Gazette, 3 July.

Peter Inch, Anthony Earnshaw, Arts Review.

Robson's Choice, Submarines crewed by ex-miners, Workers Press, 17 October.

George Melly, Anthony Earnshaw, Leeds City Art Gallery (catalogue) Leeds.

Patrick Hughes, Earnshaw, Artline.

1988

Chris Bunyan, Anthony Earnshaw assemblages and Prints, Darts, 29 June.

Robert Clark, Anthony Earnshaw, Guardian, 10 June.

Les Coleman, A View from Back O' Town, Escape No, 16, London.

Ian Breakwell, City Limits, 29 December - 5 January.

Marie-Odile Gain D'Enquin, Les Jardins Du Roi Tony, Camouflage No19, Paris.

1989

Ian Breakwell, Tomes from the Tomb, City Limits, 5-12 January.

Maria Klein, Tim Lewis & Tony Earnshaw, Art Line No.7.

1991

Terry Bennett, Drawn to Humour (catalogue) Cleveland Gallery, Middlesbrough.

George Melly, Paris and the Surrealists, Thames and Hudson, London.

Jean-Maria Wynants, Nonsense Dessurs Dessous, L'instant 4 April.

Jean-Maria Wynants, Surrealiste, n'est-il pas, ce nonsense britanique, La Sori, 4 April.

Bernice Saltzer, The Magnificent Seven, Mail 19 March.

Pru Farrier, Laughter and tears over the rainbow, Northern Echo,

W.E. Johnson, Drawn to Humour, Arts Review,

1993

Sue Hubbard, Anthony Earnshaw, Time Out.

1994

Anon., Worlds in a Box (calalogue) The South Bank Centre, London.

Xavier Canonne and Christian Bussy, Marcel Marien, Credit communal. Hainaut, Belgium.

1995

Tony del Renzio, Art Monthly.

Marie-Dominique Massoni, Eclairs d'eau, Editions Surrealistes.

1996

Robert Clark, Wall Game, Guardian 2 January.

1997

Jane Czyzelska, When I felt like it.

2000

Anon., Anthony Earnshaw, Flowers.

Patrick Hughes, Lurking in Weeds, Flowers East (catalogue).

John Slyce, 1978-2000: the Boxed Earnshaw, Flowers East (catalogue).

Glen Baxter, Observer.

Paul Hammond, Desde el Palearticp al Tropic, Phillip West: The Surrealist

Found in Saragossa (catalogue) palacio de Sastago, Zarago.

2001

Anon., Anthony Earnshaw, Yorkshire Post, 21 August.

George Melly, Anthony Earnshaw, Guardian 22 August.

Patrick Hughes, Anthony Earnshaw, Independent, 23 August.

Anon., Mr. Anthony Earnshaw: artist with eye for the absurd, Darlington and

Stockton Times, 24 August.

Anon., Anthony Earnshaw, The Times, 25 August.

Dave Robson, In death as in life, The Evening Gazette, 31 August.

Anon., Tony Earnshaw 1924-2001, The whistler Journal No. 23, Chelsea Arts Club.

T.F. Griffin, For Tony Earnshaw, Artscene, September.

Anon., Some farewell letters from Artscene, November.

2002

Les Coleman, The Rich Sardine Lives in his own Tin, Manticor No.6.

Gail Earnshaw, Anthony Earnshaw 1924-2001, Leeds Art Fair 2002 (catalogue).

2003

Robert Short, Anthony Earnshaw, Sculpture in 20C. Britain, Henry Moore Institute.

2007

George Melly, Au Nord De Quoi? No.2, editions, Bonneville, Lille.

2009

Julia Weiner, GP who has his stethoscope turned into Surrealist art, The Jewish Chronicle, 11 September

Contributions to Periodicals

1968 Surrealist Transformaction #2, (Lyle, J.), Transformaction;

The Magazine #8, I.C.A. London.

Architectural Design vol38/#12, (Pidgeon, M.), [Surrealism in the City].

1969 Evergreen Review #63, (Rosset, B.), New York.

1970 Surrealist Transformaction #1-#3, (Lyle, J.), Transformaction;

Blue Food #1, #2, (Lyle, J.), Transformaction.

1971 Surrealist Transformaction #4, (Lyle, J.), Transformaction.

1971/2 Times Educational Supplement, (with Eric Thacker), [wokker strip].

1973 Surrealist Transformaction #5, #6, (Lyle, J.), Transformaction;

Gradiva #4(special ed only), (Hondermarcq, J.), Brussels.

1974 Blue Food #3, (Lyle, J.), Transformaction;

Les Lèvres Nues #10, Brussels;

Brumes Blondes #5, (Vancrevel, R.), Amsterdam.

1975 La Fausse Sortie, Les Lèvres Nues, Brussels.

1976 Surrealist Transformaction #7, (Lyle, J.), Transformaction.

1977 Surrealist Transformaction #8, (Lyle, J.), Transformaction.

1979 Surrealist Transformaction #9, (Lyle, J.), Transformaction;

Le Cache–Sexe des Anges, Les Lèvres Nues, Brussels.

Le La #6, (Dubret, M. & Dunant, G.), Geneva.

1981 Not Poetry(Hodgkiss, P.), Galloping Dog Press;

Event #10, London.

1982 Ellebore #8, (Debenedetti, J.), Paris;

Tomahawk Supplement #2, (Gladiator, J.), Camouflage, Paris.

1983 Tomahawk Supplement #4, #5, (Gladiator, J.), Camouflage, Paris.

1984 Tomahawk Supplement #6-#8, (Gladiator, J.), Camouflage, Paris;

The Hourglass Review #1, (Wood, P.), Hourglass, Paris.

1985 Homnesies #3, (El-Janabi, A.), Paris;

Tomahawk Supplement #9, #10, (Gladiator, J.), Camouflage, Paris;

Grid #2, #3/4, (El-Janabi, A.), Paris;

De Sac et de Cord #1, (Gladiator, J.), Camouflage, Paris;

Knuckleduster Funnies #1-#4, (Egger, W. & Hesse, L.), [wokker strip].

1986 Grid #5, English contributions to surrealism, (El-Janabi, A.), Paris;

The Looker #8, (Cuthbert, D.), M5 Press;

Dunganon At Large, (Pusey, T.), Örkelljunga;

De Sac et de Cord #2, (Gladiator, J.), Camouflage, Paris.

1987/9 The Truth #1-#20, (Caplin, S.), London, [wokker strip].

1988 Annual Jissom, G.T.O.G. Huddersfield;

Extrance #2, (McGrath, A & Overton, P).

1988/9 Freedom vol49/#9 – vol50/#12, Freedom Press.

1989 Extrance #3, (McGrath, A. & Overton, P.);

Le Moment Venu, Les Lèvres Nues, Brussels.

1990 Extrance #4, (McGrath, A. & Overton, P.), Bolton;

The Looker #14, (Cuthbert, D.), M5 Press, Winscombe.

1991 Le Zérotage, Les Lèvres Nues, Brussels;

Mensuel #126, #128, Cirques Divers a Liege;

Hotel Ouistiti #11, (Gladiator, J.), Paris.

1992 Le Qui-Vive, Les Lèvres Nues, Brussels;

Terre-à-Terre, Les Lèvres Nues, Brussels.

1993 La Claire-Voie, Les Lèvres Nues, Brussels;

Hotel Ouistiti#34, (Gladiator, J.), Paris.

1995 The Whistler Journal #8, Chelsea Arts Club.

1996/9 The Whistler Journal #10-#21, Chelsea Arts Club, [wokker strip].

1997 Manticore #1, #2, (Cox, K. et al), Leeds Surrealist Group;

S.U.R.R... #2, (Massoni, M.), Editions Surrealistes, Paris.

2000 Manticore #5, (Cox, K. et al), Leeds Surrealist Group.

2001 Viridis Candela #3, Carnets Trimestriels du College de ‘Pataphysique.

2002 Manticore #6, (Cox, K. et al), Leeds Surrealist Group.

2003 S.U.R.R... #4, (Massoni, M.), Editions Surrealistes, Paris.

Contribution to books

1966

Dongdeath and Jazzabeth, Eric Thacker, Location, Leeds.

The Sycamore Tree, ( with Patrick Hughes, Robin Page and Ron Swift) hors

Commerce. ( Edition of 4).

1981

5 x 5, Trigram Press, Hebden Bridge.

1984

More on Oxymoron, Patrick Hughes, Jonathan Cape, London.

1989

Clock Lips, Marie-Odile Gain D'Enquin, Hourglass, Paris.

1990

Seeing in the Dark, Serpent's Tail, London.

1991

Six English Surrealists (concertina of postcards) |Cirque Divers, Liege.

1994

Brought to Book, Penguin Books, Harmsworth.

1996

Craven Sur Craven, Marie-Odile Gain D'Enquin, Editions du Rewidiage, Lonpre

1997

Variations on a Theme, Les Coleman, Copy Book Number 4.

1998

Redstone Diary of the Absurd, Redstone Press, London.

1999

Dying for Eternity, Andrew Lanyon, hors commerce, ( Edition of 200).

Pour Peter Wood, Hourglass, Paris.

2000

We Shall Strike for More Dreams, Peter Wood, Hourglass, Paris.

2001

Ecoutons Voir!, Leeds Surrealist Group, Leeds.

2006

Dr Clock's Handbook, Redstone Press, London.

2008

Left to write, Patrick Hughes, flowers, London; British Surrealism & Other Realitiies, The

Sherwin Collection, Mima, Middlesbrough.

2010

Pandorama, Ian Dujig, Picador, London.

2011

Paradixymoron, Patrick Hughes, Reverspective, London; Le fonds Paul Destribats, Paris; On the

Thirteenth stroke of Midnight: An anthology of British surrealism Poetry, edited by Michel Remy, Carcanet, Manchester,

Le Fonds Paul Destribats, (Schulmann, D. et al), Pompidou Centre, Paris.

2019

The International Encyclopaedia of Surrealism, Bloomsbury.

Obituaries

The Guardian: Obituary written by George Melly (22/08/01).

The Independent: Obituary written by Patrick Hughes (23/08/01).

The Times: Obituary (25/08/01).

Yorkshire Post: Obituary written by (21/08/01).

The Evening Gazette: Obituary written by Dave Robson (31/0801).

Artscene: Some farwell letters (?/11/01).

Les Colemans, farewell: Written March 2002.

Earnshaw Quotes

Gail Earnshaw:

In the pub, or around our dinner table, Tony's dramatic hand gestures, accompanied by his confident voice always caught everyone's attention. He paused, made eye contact with each guest, repeated their name and spoke. His perceptive and witty observations always rivited his audience; friend or enemy!

Before he died in 2001, I interviewed him for a book about his work.

Anthony and Gail; Earnshaw at Flowers East Gallery, London 2000

Anthony Earnshaw:

… I first saw the light of day, or for that matter the shades of night, in 1924. I was born, doubtless bawling and kicking above the family jeweller’s shop at 42 Brooke Street, Ilkley, West Yorkshire. A posthumous child, I was, my father having had the unforgivable ineptitude to go ahead and die two months before the event.The fact that I did not have a father did bother me in the early years, everyone had a dad, and I did not. This put me in the ‘outsider category', I felt cheated. I felt the odd man out and ashamed. Like all children, I wanted to be the same as everyone else. However, as I grew older, I liked being different. I began to understand that I was spiritually ‘out of step’ and felt a kinship with minority interests.

Anthony and Peter Earnshaw 1926

…1930 brought a further nosedive in the family fortunes. The shop went bankrupt and we, my mother, brother, I and Aunt Winnie moved to a council house in Redcar on Teeside, 6 Cedar Grove. It was there, summer visitors in the season, and lodgers in the windswept winters rented a room. We came down in the world. We lived there four years, happy ones for me. My most vivid childhood memories stem from then: I recall playing alone on the beach in midwinter, building sand cities, labyrinthine constructions with many streets, each with a name known only to me, indifferent to the flurries of snow whirling in the wind from the sea. I always lost my way in play before going home to Cedar Grove.’

I was walking on the beach when of a sudden a seagull must have died on the wing, up above. It crashed to the sand, plummeted at my feet, its feathers brushing my head as it did so. Taken aback I was. At the age of seven (1931) it was my first encounter with death. After all, poor old dad’s demise was before my time. There were acrid smells from the plumes of coloured smoke and at night, a glare in the sky as molten metal poured from retorts and furnace doors opened.

One of these rats is a politician 1983/86

…Despite the depression after the crash in the 1930’s we always had enough to eat, shoes on our feet and warm clothes to wear. A childhood memory that profoundly shocks me is: it was 1934, I was ten and with my mother on a shopping trip to Middlesborough. Being December snow and slush covered the ground, it was very cold, the bitter north wind blowing. Coming towards us was a woman with a shawl over her head with a little girl and boy by her side. They were aged between eight and ten and were without shoes or socks, their bare feet trudging through the slush. The look of anguish on their faces showed their suffering and desolation. The boy wore a scruffy jersey and ragged trousers. Agony and desperation were etched on their white wizened faces. This was the point where I lost belief in an economic system that allowed such things to happen. Seeing children in such a hopeless crisis shocked me greatly. It was a terrible scene, one that throughout my life has haunted me. It had a profound effect on me, being the start of a desire to contribute to changing the unfairness of our society and point out the absurdity of it.There were charities such as ‘Boots for the Bairns’ trying to help, but they were condescending and only added to the problem. Real economic reform was needed.

…when I first met Gail, she was on the Foundation Course, at Bradford College of Art, where I was working two days a week. She did stand out; all art students do, as they do not follow normal conventions of dress. They dress how they see fit and wear that which pleases them. Gail had gone out of her way to look as if she meant it. I described her as being dressed in rags with bits and pieces hanging off her in all directions and the longest hair I had ever seen in my life. It was wild. She was full of life, and a happy young girl with an obvious rebellious spirit.

Gail wanted to make the most of life and this I found attractive. People who assert their own individuality and at the same time want to share the joy of life with other people appeal to me. I recognised that she was trying to step out of the established pattern of what her life was supposed to be. Intuitively, she had the same anarchistic convictions as I. She was a natural anarchist; her background had caused her to rebel; she was an individual. Our relationship just slid into place; it seemed natural.

Anthony and Gail Earnshaw in Reeth, 1998

… I think the anarchist attitude to government is positive. It is a belief in the uniqueness of the individual who in co-operation with other unique individuals, make a society where the need for a centralised authoritarian government cast aside. All its wars, its bickering, its class division, which it generates, can be overcome and thrown away, no longer needed. It would be a rational society, one truly democratic. Everyone would be responsible for his or her own life. You would govern yourself in collaboration with others. That is the kind of society my belief in anarchism will bring about. For as long as I can remember, I have been aware that anarchism is a minority conviction and likewise, Surrealism. I am pleased for that. This may sound silly, but if we lived in an anarchist society, I would perhaps not want it and rebel against it. Essentially, I am a rebel against the established order. I do not want things the majority of people want, so I would step out of line. I need something to oppose, to show rhe absurdity of what the government thinks. Rationality is fine in education, health etc. It is essential and much used by those in authority where people are being dictatorial. Meanwhile irrationality is a marvelous weapon to question their game and bring freedom.

Guarding a used condom 1983/86

Michael Bakunin:

… If they give you ruled paper, turn it forty-five degrees and write your piece across the lines.

Robert Heinline, Science fiction writer:

… we go to work to earn the money to buy the food to get the strength to go to work … until we fall over dead.

Anthony Earnshaw:

… the Labour Party was not radical enough and Trade Unionism just a compromise set up to get a few more crumbs from the table of capitalism. It couldn’t overthrow capitalism and set in motion a new socialism, which would have been a revolution that would have changed society for the better. The working people own nothing except that which they sold to the owners of the means of production. They sold their time and skills, the only thing they owned. They were often exploited and given little reward. Governments divide humanity and by doing so bring about wars. Our economic system favours greed and selfishness that in turn gives rise to unfairness and injustice.

Anthony Earnshaw outside Bradford College of Art 1969

… I saw myself as a scruffy, working lad, no money uneducated, no talent. I’d only just started to teach myself to draw and paint from rock bottom: nothing to offer but my restlessness. Someone once asked me why I didn’t go and meet the Surrealists in Paris or Messens in London. This idea overawed me. I was a lathe turner, working in factories on piece work, trying to earn enough to feed my family.

…the works on display are subversive documents that have fallen into the wrong hands - they are mirrors on the wall that do not reflect the vampire face of commercialism. Regarding art, I am not interested in aesthetics, not concerned in making work which is reassuring, back-slapping and congratulatory. Instead, I produce work which is provocative and kicks people up the backside and makes them stop, turn and think again, of alternative ways of seeing life, themselves and the society in which they live. Surrealism for me was home. I was among friends at last, having been away in a foreign land all my life. The spell of it then cast remains a frisky imp haunting my life. Earnshaw wrote in a catalogue for his exhibition in 1966 at Leeds Institute Gallery

Trying to catch his patron's eye. 1983/86 Pen & Ink drawing (Earnshaw estate)

…It was in the late 1940s that, enamoured of Surrealism; I came to see my home city – Leeds – in a new light. Restless and not knowing what to do, I spent my Saturday evenings walking … seeking, I suppose, some avenue of astonishment. (Occasionally I was in the company of another but most frequently alone.) These walks were in fact, elaborate games. From some arbitrary starting point, I would walk to the other side of town using, as far as possible, only back, streets and side-roads – secret passages of yet another species. Again, other evenings were spent tram-riding. I boarded and alighted from trams at random for two or three hours. It was my custom to carry a book to read on these swaying, nocturnal journeys. It was only later that I learnt that the Surrealists had engaged in very similar activities in Paris in the 1920”s.

… After my exhibition, I was fortunate to be given a day a week at Harrogate Art School, then two days at Bradford Regional College of Art. One day paid as much as working a month in the factory. I liked working with like-minded people and talking about my work. Art students learn by making things. Academic pursuit is secondary. Co-operation and working together are the key to education. Earnshaw

… 'Back O’ Town' comes from Louis Armstrong’s 1930s recording 'Back O’ Town Blues'. This is the place where all true poets and artists view the world and their situation. It’s a secret place known possibly to the imaginative.

Catalogue for Anthony Earnshaw retrospective at Leeds City Art Gallery 1987

... the artist, writer and critic, Toni Del Renzio reviewed the exhibition, Worlds in a Box, 1995, an Arts Council touring exhibition:.

Toni Del Renzio:

Anthony Earnshaw follows Duchamp in the catalogue but deserves that place not merely by alphabetical chance. With characteristic surrealist verve, he offers a hostage to fortune with “The Bride with her Batchelors again,” after Marcel Duchamp. Earnshaw is one of the very select band of Surrealists in this country who has quite consistently pursued his research without succumbing to either camp modishness or superficial whimsy and who is not overwhelmed by Joseph Cornell and Maurice Henry.

Anthony Earnshaw:

…Toni del Renzio, declaring that I am in the company of such people like Duchamp, whom I respect and admire, pleases me enormously. I’m pleased that he says I am a strong image maker in my own right although influenced by others and recognises that I have made unique images which stand in their own right and do not plagiarize others. Earnshaw in response to Del Renzio’s review.

The Bride with her Bachelors stripped bare: after Marcel Duchamp, 1991 Boxed Assemblage 45x40x10cm ~(Earnshaw estate)

…Charlie Chaplin cocked a snook at opposing authority; he was a black humorist.

Modern Times is one of the great films of all time. It is about the triumph of the little isolated man, coping with a big wide world of which they have little control. Chaplin showed how absurd this is as in his film. Charlie is in a huge, impersonal factory working on a mass production line with a spanner, whose job it is to tighten one nut as they go past on a production line. Tony points out, ‘Can you think of anything more absurd that that. It existed in the thirties in Henry Ford’s Detroit car factories. This behaviour still exists. t is absurd in the true sense of the word, meaningless; degrading and insulting what human beings have to offer. It is negative and offensive to think that civilisation has come to this. Chaplin is a hero because he pointed out how absurd a society was Which allowed such things to happen. We both admire him. He was the underdog, the man being used as we all are by capitalism, our humanity is taken away from us and we become things to be used and exploited and when no longer needed discarded and thrown away. Chaplin was heroic to talk about this, especially in America where capitalism triumphs. They conspired together to try to ban the film but were unsuccessful. They did not like someone such as Chaplin citicising their attitudes in a meaningful way.

Hitler tried to ban Paul Klee’s paintings because he thought they were decadent and might be dangerous. It is the same attitude that existed many years ago; do not teach the masses to read and write lest they use their knowledge to rebel. Education should alert people and help them to be free. Freedom is the realisation that because of your attitude and deep held convictions, you feel you want to contribute yourself, to share your visions with others. It is no usebeing free if you do not have anything to say. You have to want to join in and contribute to an ongoing adventure of being alive. Chaplin was free with others each in their unique way, trying to do that.

Andre Breton tried to do it with his Surrealist manifesto. He tried to reveal to himself what he thought of as liberty and freedom, and he wanted to share it with others, which he tried to do through his first Surrealist manifesto. This is on the same level as Chaplin’.

Jazz is different; it is a collective thing. Nevertheless, various bands tried to do it. There is a race issue in jazz. I feel free when I listen to jazz. Slavery is distanced, and in addition, these people standing up and defiantly fighting for their right to exist is marvellous. Trying to affirm and assert oneself, making one's own music and poetry without being told to do it by others is important. Bessie Smith sang the blues about the rough life she lived and the individuality of being a ‘dirty nigger ’as white people referred to her as being. She tried to cope with life with a strong powerful voice of confidence, condemning society for generating such misfortune. She was the victim of a car crash and left to die because she was black, two hospitals refused her before she died. One of the tragedies of the 20th C. A disgrace.

…… This quote is an Earnshaw response to a questionnaire sent to him by the Paris Surrealist group, ‘SURR’ (Surréalisme, Utopie, Rêve, Révolté). It was an inquiry asking if dreams playa role in his written and visual work.

Anthony Earnshaw:

...To tell the truth, dreams play little if any part in the life of either my written or my visual images. The daydream is the source from which they spring, my images come to life in my head and often father a family of related images each clamouring for attention. Humour, if not black, then certainly charcoal grey is the engine driving my productivity, humour put to use as an ‘innocent weapon’ to subvert banality and overturn the ‘apple-cart.’ (Golden-Delicious – tasteless! However, having said that, when I was a young man, soon after the Second World War and incidentally, just after I had discovered Surrealism, I had a dream featuring a powerful image that dominated my mind for many years. This image was, while simple in itself sinister and gripping, it depicted the severed head of a wolf biting a rope with its teeth: the rope stretched from a window in a dark, otherwise featureless brick wall. It was twilight; a wind was blowing, making the rope and the wolf’s head sway. I once described my dream to a friend versed in psychoanalysis. He declared the image probably stemmed from the trauma of birth, the severing of the umbilical cord.”

… After publishing Musrum, newspapers and the Sunday press reviewed it. One critic, Ivor Cutler,the poet, asked to review the book, and he was critical of it. Cutler thought it whimsical. Later, since those days, I met Ivor Cutler, and we became firm friends. I would have preferred ‘black humour’, ‘whimsical’, to me is superficial, trite, of no real consequence. It does not take into account a serious attack on convention. My work is more than whimsical. It presents an alternative viewpoint that is very serious and challenges the ordinary and the accepted which is usually dictated to us by others who go along with it without seeing the need to challenge and change it. Walt Disney is whimsical, but such as Magritte, Bunuel, Ernst, they are not whimsical, they present a poetic view of the world. My drawings and my cartoon strip Wokker, attack existing culture and kick it in the pants, it dismantles it. Musrum is perhaps a flight of fantasy, I do not mind the word ‘fantasy’ not a word I am very fond of but it is the correct word to describe Musrum and Wintersol. There is certain seriousness in Musrum, essentially it’s in the tradition of the quest for the Golden Fleece, and it’s the quest to find a marvellous treasure that is essential and it’s gone astray. The story is about the adventures Musrum encounters during his quest to regain his lost treasure. I think that is a basic concept of a fairy story of a legend and as such, I am not ashamed of it. It is quite an admirable story.

Musrum (with Eric thacker) 1968 Jonathan Cape. Wintersol (with Eric Thacker) 1971 Jonathan Cape.

…Wokker is an extraordinary bird-like creature, who has wheels for feet; a mischief-making “mercurial hero” - an innocent abroad, “dismayed by the prospect of existence.”

Wokker Strip

Les Coleman, editor, Anthony Earnshaw The Imp of Surrealism RGAP 2011:

… With its many voices, views, and opinions, this book offers a comprehensive overview of the work of the artist and autodidactic, Anthony Earnshaw (1924-20010. As a free-thinking maverick, Earnshaw preferred to plough the marginalised furrows of an art world, to which he maintained a distant ambivalence. Influenced by Surrealism, Jazz and poetry in postwar Britain, his restless and rebellious temperment would find spiritual reassurance in the principles and philosophy of the anarchist movement.

As a nonconformist, at odds with the values of Western capitalism, Earnshaw recognised that to explore his imagination was liberating. He embarked on a lifetime of creative activity which found form in an extraordinary range of work including: drawings, paintings, poetry, and writing, comic strips and illustrated novels, boxed assemblages and constructed letterforms.

Anthony Earnshaw The Imp of Surrealism RGAP 2011

Chronology

ANTHONY EARNSHAW- CHRONOLOGY

1910

- Paternal grandfather murdered in Bradford, West Yorkshire.

1921

- Peter Earnshaw, older brother of A.E., born.

1923

- The Industrial Workers of the World or Wobblies which were founded in 1905 was at its peak. The IWW contends that all workers should be united within a single union as a class and that the wage system should be abolished.

1924

- Born in Ilkley West Yorkshire, at 42 Brooke Street on 9 October, the second son of Ernest Earnshaw, and Dorothy Earnshaw. Ernest Earnshaw dies after developing meningitis and pneumonia, two months before A.E.’s birth.

Tony (left) Peter (right)

- Franz Kafka dies in Prague, Lenin dies in Russia and André Breton published his first Surrealist Manifesto in Paris.

1930

- The family Jewellery business in Ilkley is declared bankrupt. Dorothy Earnshaw, Peter, Tony and Aunt Winnie, Dorothy’s sister move to 6 Ceder Grove, Redcar, a small seaside town on the North Yorkshire coast.. A.E, and his brother attend John Batty Primary School, Redcar.

1931

- Fred Myers, A.E.’s maternal grandad retires and moves from Ben Rhyding with his wife Alice to live in Saltburn by the Sea to be near their daughter Dorothy and their grandsons.

1933

- The film ‘King Kong’ is released. Seen by A.E., it makes a profound impression and Kong will feature in his art many years later.

Prince Kong Distracted From His Toys by an Apparition of Fay Wray in the Guise of a Fairy 1996 pen and ink and crayon 52.5x68.5cm~ (private collection)

1934

- The Earnshaw family move to 33 Spencer Place, Leeds.

1936

- A.E. and his schoolfriends watch in fear as a German airship passes over Harehills School.

- A Diptheria epidemic breaks out in Leeds. A.E., who suffers from severe bronchitis, is briefly moved from Leeds to live with his grandparents in Saltburn by the Sea. He attends Saltburn School.

1938

- Leaves Harehills school at Easter to work as an apprentice fitter and lathe turner at Ingleby Motors, Leeds where Peter has worked since 1935.

- A.E. develops an interest in the history and origins of New Orleans jazz and blues.

1940

- Meets Eric Thacker at Leeds Rhythm Club. As well as jazz, they both have an interest in Surrealism. A mutual interest in New Orleans Jazz and Surrealism. The friendship lasts until Eric’s death in 1997.

Eric Thacker

1942

- On 9th October 1942, A.E.'s birthday, he receives call-up papers. Graded C3, unfit for active service, due to ill-health.

1945

- A.E. publishes a letter in Freedom inviting anyone interested in anarchism in Leeds/Bradford area to make contact with the idea of forming an anarchist discussion group. There is no support for the proposal.

1946

- A.E. writes a poem about Ingleby Motor Company which he puts on the factory noticeboard, for which he receives the sack.

1947

- The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, is established by Roland Penrose.

- Meets George Melly at the London Gallery, Brooke Street, London, where Melly works. This is the beginning of a loyal friendship in which Melly will later become a collector of A.E.,’s work. Starts to make small drawings and collages.

Anthony Earnshaw with George Melly at Dean Clough Gallery, Halifax, 1998.

Talking about his exhibition, 'Because I felt Like it'.

1950

- First exhibition with friends in a shoe shop on Briggate, Leeds. A.E: “We put our work up on the walls between the shoe racks.”

- Visits the ICA, London, where he briefly meets Roland Penrose to show him an early drawing. Penrose looks at it perfunctorily before leaving for a meeting.

1956

- Works at Leeds College of Art as a part-time portrait model. Meets Monica Simpson, who attends evening painting classes.

1957

- Marries Monica Simpson in March at St Augustin’s Church, Leeds. They move to 64 Northbrook Street, Leeds.

- Birth of daughter Ruth Mary Earnshaw on 15 December, in Leeds.

1959

- Birth of daughter Frances Jane Earnshaw on 9 January, in Leeds.

1960

- Starts to make larger paintings

Bed End, oil and sand

Bed End, oil and sand

1961

- Meets the artist Patrick Hughes in The Wrens Pub, Leeds. They become close friends, a friendship that continues until A.E’s death.

Anthony Earnshaw and Patrick Hughes Flowers East 2000

1964

- Melly gives a lecture on Magritte at Leeds College of Art, and later with Patrick, visits 64 Northbrook Street, Leeds, where he purchases a painting by A.E.

1965

- Makes his first assemblage using a found object, after discovering a bayonet socket with only one slot in it for the bulb to fit in. E.: “ I wired it up using a piece of flex attached to a lamp-holder and put it on a backing tp represent the ceiling. It ceased to be a mass-produced utilitarian object because it was flawed. I gave it a new identity”.

Found Object, 1965 (private collection)

1966

- Re-establishes contact with Eric Thacker and they start corresponding regularly. The germination of ‘Musrum’ and ‘Wokker’ date from this time.

- Dorothy Earnshaw dies in Ben Rhydding, Ilkley. She is buried in Ilkley cemetery, next to her husband, Ernest Earnshaw.

- Collaboration with Patrick Hughes, Robin Page, Ron Swift to collect and name leaves taken from a sycamore tree in Gledhow Valley Woods, Leeds. Four hand-printed copies of The Sycamore Tree were made. Trevor Winkfield: “Under Earnshaw’s supervision, we coated each leaf with ink and pressed them against sheets of paper. At the end of an exhausting day, we bound the sheets into a book: Earnshaw’s portrait of a tree. It was a wonderful conceit, using both the subject and its fundament, wood, to make the leaves of a book.

Tony making the Sycamore Leaf book

- ‘Painting 1945-1965’, Institute Gallery, Leeds: an exhibition of eighty oil and watercolour paintings organized by Patrick Hughes. The success of the exhibition enables A.E. to stop working as a lathe turner and start working as a lecturer one day a week at Harrogate College of Art.

The Castle where the Birds Live 1953, Watercolour on paper (Dean Clough Art Gallery Collection)

1967

- Starts teaching two days a week at Bradford College of Art in the Textiles Department.

- Exhibits work in ‘The Enchanted Domain’ exhibition in Exeter, organised by John Lyle; their friendship continues until A.E. death.

1968

- Contributed to Surrealist Transformaction, edited by John Lyle.

- Musrum, in collaboration with Eric Thacker, is published by Jonathan Cape, London.

- Teaches on foundation Course at Bradford College of Art, with Jeff Nutall, Alistair Park and Roddy Carmichael, with Albert Hunt running complementary studies. Participates in ‘festival of chance’ where he shows the film ‘King Kong’ backwards. Other participants in the festival include Robin Page, John Latham and Bruce Lacey.

- Meets Gail Blackstone, a student on the Foundation course.

Anthony and Gail Earnshaw, Reeth, North Yorkshire 1998

1970

- Exhibits original ‘Wokker strips’ in ‘Comics’ at he ICA, London.

1971

- ‘Wokker’ appears weekly in the Times Literary supplement , then in The Times Educational Supplement from 8 October, for one year.

- Wintersol, in collaboration with Eric Thacker, is published by Jonatan Cape, London.

- Patrick Hughes untroduces A.E. to Angela Flowers and her gallery.

- Awarded a fellowship at the Department of Fine Art . A.E. is contracted to teach there two days a week which continues until 1985.

- Takes part in a Street Performance in Leeds with Fine Art Students. They are arrested for disturbing the peace and, along with the other members of the group, A.E. is given two years suspended sentence.

1972

- Seven Secret Alphabets published by Jonathan Cape, London. Exhibition at Angela Flowers Gallery, London of alphabet prints and original pen and ink drawings combined with the book launch.

1973

- 25 Poses published privately with the aid of Yorkshire Arts Association grant.

- ‘Hughes & Earnshaw’, show at Ferens Art Gallery, Hull.

1974

- Paints Wokker’s portrait . Exhibited at Cartwight Hall, Bradford.

Nightwork: Wokker's eyesight Fails while He is Guarding a Factory on a Tray 1974 Watercolour 79x57cm~(private collection)

1978

- ‘Dada and Surrealism Reviewed’, Hayward Gallery, London. Angela Flowers Gallery, London mounts ‘Transformaction Review,’ to coincide with Hayward Gallery exhibition.

- Declines to take part in ‘Surrealism Unlimited 1968-1978’, Camden Arts Centre, London on ideological grounds.

1979

- Exhibits in touring exhibition ‘…a cold wind brushing the temple’ showing works purchased by George Melly for the Arts Council of Great Britain.

1981

- 5 x 5 an anthology edited by Asa Benveniste, published by Trigram Press, Hebden Bridge. Contributors are Anthony Earnshaw, Glen Baxter, Ivor cutler, Ian Breakwell, Jeff Nuttall.

- Flick Knives & Forks published by TRANSFORMAcTION, Harpford.

1983

- Meets artist and poet Peter Wood in the Nags Head Pub, Leeds. Originally from Yorkshire, Wood was now residing in Paris.

1984

- Visits Marcel Mariën at the time of the Marien exhibition ‘Mise en oeuvres’, Galerie Isy Brachot, Brussels.

1985

- Marries Gail Blackstone, 5 Jan 1985 at Leeds Registry Office.

- Carping & Kicking, published by Hourglass press, Paris.

1986

- Contributes to ‘Contrariwise:Surrealism and Britain 1930-1986’, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea.

1987

- F.O.E. (Friends of Earnshaw) buy and donate ‘Raider’s Bread’ to Leeds City Art Gallery.

Raider's Bread 1979 Mixed media assemblage 34x24x12cms ~(Leeds City Art Gallery)

- Attends lecture given by Sir Roland Penrose. during question time, A.E. asks Penrose to explain how he could accept a knighthood from the establishment while claiming to be a surrealist. After a long silence, Penrose says he will discuss the matter in private, an offer he reneged on.

- Retrospective Exhibition ‘View from Back O Town’, Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds and Cleveland Gallery, Middlesborough.

A View From Back 'O Town Exhibition Leeds City Art Gallery, 1987

- An eighteen-minute film on A.E. and his work, by Alex Marengo, is screened as a Saturday Review special, ‘Two English Surrealists’, on BBC 2, 10 October.

1988

- An Eighth Secret Alphabet, published by Hanborough Parrot Press, Oxford.

- Aspects des Bas-Quartiers’,published by Camouflage Press, Paris.

- ‘Works ancient and Modern’, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, Edouardo Paolozzi is exhibiting in the adjoining gallery, and they exchange works.

- Wokker Exhibition at Dean Clough Gallery.

1989

- Clock Lips, by Marie –Odile Gain d’Enquinwith illustrations by A.E. published by Hourglass Press, Paris.

- A ten-minute film, ‘On the Edge,’ showing A.E. and his work is screened on Tyne Tees TV, December 7th.

- Moves from Leeds to 4 Emerald Street, Saltburn by the Sea with Gail who is employed by Cleveland gallery, Middlesborough, A.E. has his own studio for the first time.

1991

- ‘Funny Looking’, – Cirque Divers, Liège; an exhibition of six English surrealists organised by Les Coleman. A.E. is among the exhibition contributors who visit Marcel Mariën in Brussels.

1992

- ‘Portrait of the Artist’s Mother Done from Memory’, Angela Flowers Gallery, London, is the result of a suggestion by A.E. and Ian Breakwell.

In Memorium:Dorothy Rose Earnshaw Nee Myers:( Born 1891-Died 1963) 1992 Watecolour on paper 80.5x52cms ~(Earnshaw estate)

1994

- Exhibits in ‘Worlds in a Box ‘(The South Bank Centre touring exhibition) travelling to Edinburgh, Sheffield, Norwich, and Whitechapel Art Gallery, London.

- Gail and A.E. visit André Breton and Benjamin Pèret’s graves in Paris

- A.E.’s health starts to deteriorate, and he has several spells in hospital.

1995

- Exhibits in ‘The Discerning Eye’, Mall Galleries, London at the invitation of Patrick Hughes.

- Makes a second visit to Batignolles cemetery, Paris, where Breton and Pèret are buried. The inscription on Pèret’s grave reads: ‘Je ne mange pas de ce pain-là.” this translates as “I do not eat that bread!” and was the title of a collection of his poems published by Éditions Surrealists in 1936. A.E. Gail and friends place a piece of bread on his grave.

Batignolles cemetery, Paris

1997

- Visit Chicago with Gail for A.E.’s exhibition ‘I only want to Help’ at Belloc Lowndes fine Art Gallery, Chicago. While there they visit the surrealist collection at the Art Institute in Chicago and the collection at the University of Chicago.

- Flick Knives and Forks (second edition), published by Zillah Bell Contemporary Art Gallery, Thirsk.

1998

- Peter Earnshaw dies of Parkinson Disease

2000

- ‘Anthony Earnshaw. Selected Works from the last 20 Years,’ Fowers East, London. This was the last exhibition A.E. attends.

2001

- John Clayton visits 4 Emerald Street, Saltburn to make his film Flick Knives & Forks.

- Despite being seriously ill in hospital A.E. sees Wokker animated by Dave Brunskill shortly before his death. Dies from cancer of the colon on 17 August, in James Cook Hospital. Buried in Saltburn Cemetry. On his gravestone, is carved the words, ‘Sudden Prayers Make God Jump!’(an aphorism from Musrum) together with crossed-fingers, forming the letter X from one of his secret alphabets … just in case!

- Memorial exhibition at Leeds City Art Gallery. An exhibition of his, and friends work, in A.E and Gail’s private collection.

2002

- ‘Earnshaw & Friends’ Dean Clough Art Gallery, Halifax showing works from the permanent collection of Tony and his friends.

- John Lyle dies in France in August.

2003

- John Clayton’s short film completed.

2005

- 'Boxes’, Flowers Central, London, exhibition. John Clayton’s film shown for the first time.

2007

- Hay on Wye Flick Knives & Forks film shown by Ken cox

2007

- Ilkley Literature Festival talk by Ken Cox ‘A Surrealist against the Grain’.

2011

- ‘The Imp of Surrealism’, exhibition, Flowers, London.

- Anthony Earnshaw The Imp of Surrealism, edited by Les Coleman, is published by RGAP.

photo by Michael Woods

2009

- ‘Anthony Earnshaw, his Life and Work’, a talk by Gail Earnshaw at Chapel Allerton Library, Leeds.

2012

- The Tate purchase a collage, A.E. made in 1948.

Untitled collage 1948 ~(Tate collection)

2016

- The Anthony Earnshaw Bursary is set up by Patrick Hughes in memory of A.E. It provides assistance towards costs for students studying Acess to HE diploma(Art & Design) at Leeds College of Art.

2017

- ‘The Imp of Surrealism’, exhibition at Cartwright Hall, Bradford.

- Gail Earnshaw talks about A.E., and his work at Cartwright Hall, Bradford.

- The Distribution of Wishes’, exhibition at Vernon Street Gallery, Leeds college of Art.

- Dawn Ades talks about A.E.'s work.

2018

- S for Spellbound a talk by Ken Cox at Inkwell, Leeds.